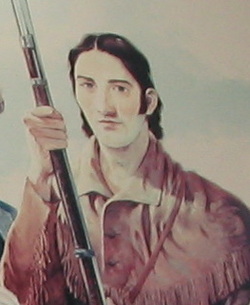

I was looking for an image of David Crockett to post on his 227th birthday, and ran across this detail from a mural in the Franklin County Library, in Winchester, Tennessee. Winchester is ten miles northeast of the frontier neighborhood where David and Polly Crockett were living in the summer of 1813, just before David volunteered to fight in the Creek War.

This David's features are borrowed from portraits made during his political career (the only images from life we have), but the muralist has given him a young man's face. You can imagine him setting out to serve under General Andrew Jackson against the Creeks. Or you can imagine him -- as I did -- as a frontier hunter, heading out in search of game to feed his family.

He was a much better hunter than farmer, but he had to work some rented acres just the same. Tradition in the Bean's Creek neighborhood holds that, if you know the right place to look, you can walk out into the middle of a field and see a well that David Crockett dug 200 years ago. When I was reporting Born on a Mountaintop, I got to do just that. My guide was a local man named Jim Hargrove, who had retired in a spot just a few hundred yards from the well. Its square concrete top, Jim told me, was added long after Crockett's time. But when I peered down into the well itself, it looked suitably old.

This David's features are borrowed from portraits made during his political career (the only images from life we have), but the muralist has given him a young man's face. You can imagine him setting out to serve under General Andrew Jackson against the Creeks. Or you can imagine him -- as I did -- as a frontier hunter, heading out in search of game to feed his family.

He was a much better hunter than farmer, but he had to work some rented acres just the same. Tradition in the Bean's Creek neighborhood holds that, if you know the right place to look, you can walk out into the middle of a field and see a well that David Crockett dug 200 years ago. When I was reporting Born on a Mountaintop, I got to do just that. My guide was a local man named Jim Hargrove, who had retired in a spot just a few hundred yards from the well. Its square concrete top, Jim told me, was added long after Crockett's time. But when I peered down into the well itself, it looked suitably old.

Hargrove, as it happened, helped take care of another important Crockett site in the neighborhood -- one that puts a bittersweet edge, in hindsight, on that last, pre-war summer that David, Polly and their two young boys shared in Tennessee.

David signed up to fight Indians in September 1813. Polly pleaded not to be left alone, but he felt he had to serve. He was home a few months later, his enlistment up, but before long he enlisted again. The Creek War was over, but the War of 1812 was still going on, and, as Crockett would explain years later in his autobiography, "I wanted a small taste of British fighting." Once again, Polly protested, and once again, her restless husband ignored her. "I always had a way of just going ahead, at whatever I had a mind to," he wrote, with commendable honesty but little apparent remorse.

Within a few months of his return home -- the chronology gets a little murky here -- David had a third child and Polly was dead. It's not known what killed her, but one of the many possibilities, or perhaps a complicating factor, was simple malnutrition. Bean's Creek tradition reinforces this possibility. When David was off fighting, Hargrove told me, Polly and the children didn't have enough to eat, and they'd have had even less if a Cherokee man who lived nearby hadn't shared some of his own food.

She's buried in what's now known as the Polly Crockett Cemetery, high on a ridge a mile or so east of David Crockett's well. A grove of trees gives the place an isolated feel, as though it were its own private hilltop. A good number of Jim Hargrove's mother's relatives are there as well.

David signed up to fight Indians in September 1813. Polly pleaded not to be left alone, but he felt he had to serve. He was home a few months later, his enlistment up, but before long he enlisted again. The Creek War was over, but the War of 1812 was still going on, and, as Crockett would explain years later in his autobiography, "I wanted a small taste of British fighting." Once again, Polly protested, and once again, her restless husband ignored her. "I always had a way of just going ahead, at whatever I had a mind to," he wrote, with commendable honesty but little apparent remorse.

Within a few months of his return home -- the chronology gets a little murky here -- David had a third child and Polly was dead. It's not known what killed her, but one of the many possibilities, or perhaps a complicating factor, was simple malnutrition. Bean's Creek tradition reinforces this possibility. When David was off fighting, Hargrove told me, Polly and the children didn't have enough to eat, and they'd have had even less if a Cherokee man who lived nearby hadn't shared some of his own food.

She's buried in what's now known as the Polly Crockett Cemetery, high on a ridge a mile or so east of David Crockett's well. A grove of trees gives the place an isolated feel, as though it were its own private hilltop. A good number of Jim Hargrove's mother's relatives are there as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed